CASS Fortnightly Update

23 November - 6 December 2023

Home -> Weekly Update -> CASS Fortnightly Update 23 Nov – 06 Dec 2023

Contributing information sources to this document include public and non-public humanitarian information. The content compiled is by no means exhaustive and does not necessarily reflect the position of its authors or funders. The provided information, assessment, and analysis are designated for humanitarian purposes only and as such should not be cited.

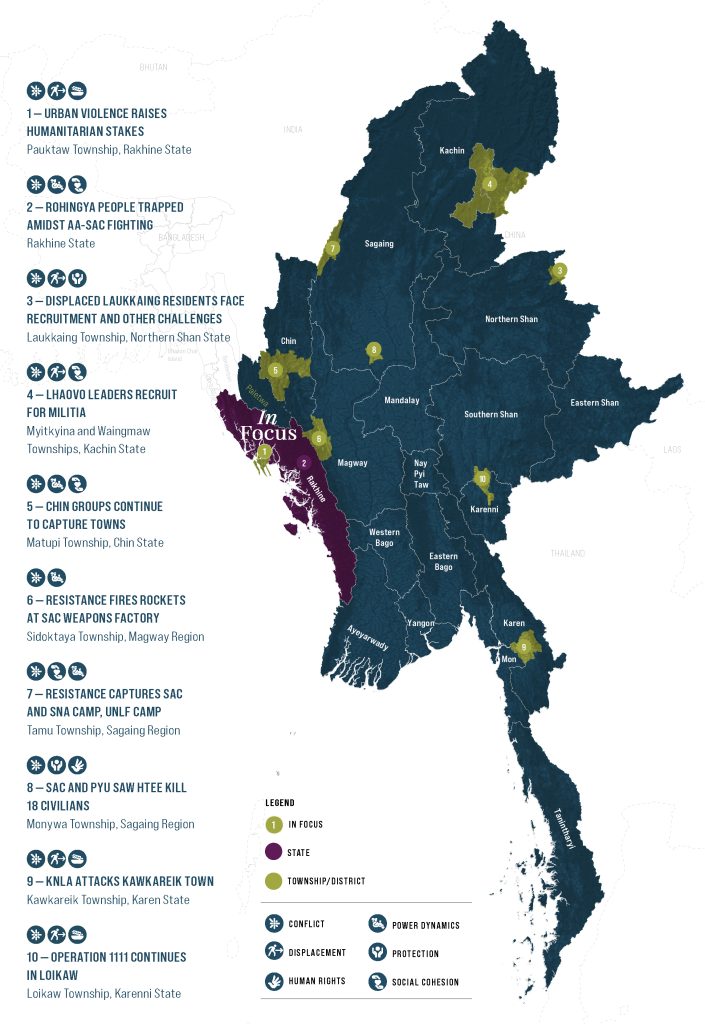

In Focus

1 .Urban Violence Raises Humanitarian Stakes

Pauktaw Township, Rakhine State

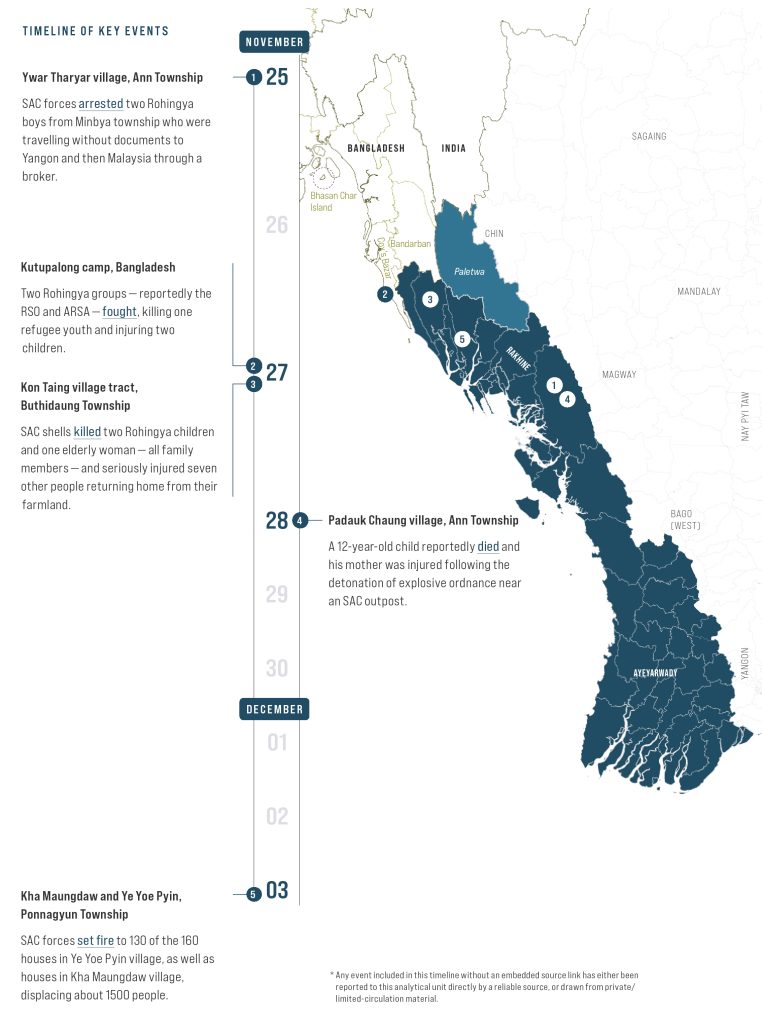

Over the past fortnight, intense fighting in Pauktaw town (in Pauktaw Township) has continued to displace civilians. As discussed in the last Fortnightly Update, State Administration Council (SAC) troops re-entered the town on 15 November and launched a barrage of airstrikes and artillery shells, after media claimed that the Arakan Army (AA) had gained control of the town and entire township that morning. The SAC reportedly detained town residents in order to deter AA attacks. This fighting has continued, involving SAC ground troops, fighter jets, and shelling from navy vessels. During fighting in the town on 23 November, AA fighters reportedly killed 18 SAC soldiers and rescued at least 104 trapped residents. On 29 November and 1 December, the AA allegedly rescued more town residents. The vast majority of residents have fled: on 29 November, a member of local CSO network Arakan Responders for Emergency told local media that fighting over the prior two weeks had displaced nearly 200,000 people in Rakhine State, including over 70,000 in Pauktaw Township. On 29 November, a parahita worker in Pauktaw Township told local media that displaced people needed rice, and that a transportation shutdown made it difficult for aid groups to reach affected people.

The fighting around Pauktaw has taken place within a wider escalation of armed violence in at least seven townships in northern and central Rakhine State, as well as in Chin State’s Paletwa Township, since 13 November. On 24 November, fighting broke out in Myebon Township, and local media reported that intense hostilities and SAC airstrikes continued near Ta Run Aing and Hnone Bu villages in Paletwa Township. Local media reported on 25 November that the two sides were fighting fiercely after the AA launched an offensive against an SAC Border Guard Police (BGP) outpost near Kaing Gyi village in Maungdaw Township. On 28 November, the AA attacked and seized a BGP outpost near Baw Hti Kone village in Maungdaw Township. Both camps are located along the Ah Ngu Maw-Maungdaw highway, which is important for Maungdaw border trade and control. Sources reported to this analytical unit that AA has taken control of the highway from Angu Maw to Tha Win Chaung village. On 4 December, after 21 days of fighting in Chin State’s Paletwa Township, the AA reportedly captured the SAC’s Ta Run Aing hill position, one of two SAC positions located in strategic proximity to the Indian border.

Fighting continued to displace both rural and urban residents of Rakhine State and Chin State’s Paletwa Township. On 23 November, BBC Burmese reported that residents of rural Ta Run Aing and Hnone Bu villages in Paletwa Township had fled their homes due to ecalating fighting. On 27 November, local media reported that residents of Ye Yon Pyin, Kha Maung Taw, Kyauk Siek, Yoe Ngu, and other villages in Ponnagyun Township had fled due SAC artillery and drone fire hitting their villages. On 27 November, local media reported that residents of Minbya Township’s Pan Myaung village — near which there is an SAC hilltop outpost — moved to areas near the upper Laymro river due to fear of potential fighting. On 2 December, more than 6,000 residents from Dar Let and Ka Zu Kaing village-tracts in Da Let Chaung area, Ann Township, fled due to artillery shells from the SAC’s Light Infantry Battalions 371, 372, and 374. On 3 December, SAC forces reportedly fired on Ye Yon Pyin and Kha Maung Daw villages in Ponnagyun Township (both near Sittwe Town) — where the SAC also burned down nearly 200 houses, displacing approximately 1,500 residents.

Urban blight

A considerable proportion of the recent armed violence in Rakhine State and Paletwa Township has taken place around urban areas, with severe consequences for more densely populated areas that also serve as market hubs for rural populations. Outside of Pauktaw, most of the violence in towns has been perpetrated by the SAC alone, as the AA has generally not launched attacks near these locations. However, such intense urban violence is a new dynamic not seen in previous rounds of active fighting in western Myanmar, and has resulted in a reversal of IDP flows, as IDPs previously sought shelter in urban areas, which were seen as safer. The movement of IDPs to disparate rural locations will make the delivery of aid more challenging. Pauktaw town is largely empty, and BBC Burmese reported on 27 November that 90 per cent of Minbya town residents had fled due to shelling from nearby SAC bases and fear of fighting in the town. Following reports of fighting near Paletwa town on 28 November, town residents told this analytical unit that they were concerned urban armed violence could erupt in the town, as it had done in Pauktaw town, and that some residents had already fled to rural areas. Because towns are densely populated, fighting within their boundaries is likely to affect far more people than rural armed violence, and as people flee from towns, displacement numbers are expected to be much higher. Additionally, towns typically function as the marketplaces for surrounding communities, with at least two implications: urban fighting could threaten the operation of these markets for those within the wider area; and people who flee far from these towns may not have easy access to markets.

Even where markets should be able to function, SAC shelling and other actions have disrupted market access. On 4 December, SAC troops burned down a market in Pauktaw. Local media reported on 24 November that SAC artillery shells set the main town market in Ponnagyun ablaze, destroying over 300 shops. Ponnagyun residents told this analytical unit that the SAC is intentionally targeting urban markets to cut off food supplies for Rakhine people and the United League of Arakan (ULA)/AA, and that the SAC is targeting civilians as retaliation for AA attacks against the SAC. Whether or not these claims are true, urban populations are now being significantly affected by the ongoing fighting and may experience further disruptions to their daily lives, economic activities, and access to essential services. Meanwhile, the complete or partial closure of major markets in towns has also likely made it harder for local responders to procure goods for rural populations in need. Sources reported to this analytical unit that host communities, some local aid groups, and the ULA/AA were assisting people recently displaced from Pauktaw town, but were facing supply challenges, with shortages in local markets. Under the current circumstances — with fighting and overt restrictions standing in the way of much movement — displaced populations, as well as communities throughout the state, are under particular strain.

Rural populations in need, out of reach

SAC restrictions have made it much more difficult to provide humanitarian assistance to the tens of thousands of newly displaced people, even as those already displaced have struggled to survive with minimal support. The SAC’s closures of roadways and waterways within (and leading into) the state have contributed to rising prices for food, fuel, and other commodities. On 29 November, local media reported that one million residents in Rakhine State were facing shortages of food supplies — notably rice — following the SAC shutdown of transportation within the state. Daily wage labourers in Kyaukpyu Township were said to be boiling and eating broken rice, and Maungdaw town residents could not find rice — a bag of which reportedly cost 180,000-240,000 Myanmar Kyat (~ 84.79-113.06 USD), depending on type — due to shortages. On 19 November, local media reported that previously displaced populations in Rathedaung, Ponnagyun, Kyauktaw, and Mrauk-U townships were facing shortages of food supplies. Recently displaced people from Pauktaw town reported to this analytical unit that they were facing challenges related to sanitation and hygiene, food supplies, and shelter. At the same time, fighting and insecurity have also undermined the ability of people to harvest rice and other crops, including by displacing farmers, thinning out the labour pool, and driving up the price of conducting agricultural activities. On 28 November, local media reported that rice milling machines in rural villages, including in Ponnagyun Township, were no longer operational due to fuel shortages and rising prices, resulting in rice shortages in the villages. By curtailing harvesting and production, fighting has further worsened food security.

Despite these escalating needs, humanitarian responders remain stymied by overt restrictions and other challenges. With the resumption of fighting on 13 November, the SAC immediately shut down the three main roads connecting Rakhine State to neighbouring Magway, Bago, and Ayeyarwady regions. This is particularly concerning as high quantities of food and medical supplies used in the state had been transported from central Myanmar. The SAC also quickly shut down the main road connecting Sittwe and Ann townships, blocked civilian water transportation, and blocked the roads into towns in Gwa, Taungup, Thandwe, Kyauktaw, Mrauk-U, Rathedaung, Ponnagyun, and Sittwe townships. Even if these routes were to open, international responders would still need SAC permissions to deliver assistance, and local responders would still be operating under a shroud of suspicion from the SAC, if not also the AA, and would be potentially vulnerable to detention or worse. In addition, security concerns — including airstrikes, artillery fire, landmines and other unexploded ordnance and gunfire — would likely continue to pose barriers to assistance as long as fighting continued. In any case, however, the delivery of assistance through local responders remains the most effective means of helping populations in need in Rakhine State.

Solutions evasive

As the AA ramps up attacks in Rakhine State in the context of wider fighting in Myanmar since the launch of Operation 1027, and as long as the SAC is unwilling to cede control in Rakhine State, there is no immediate resolution in sight. The AA has long fought for greater control and autonomy in the state, and may have been emboldened by the territorial gains made in Northern Shan State as part of Operation 1027. The SAC, meanwhile, is fighting to retain what control it retains in western Myanmar, where the losses of border trade and vested economic interests such as the Kyaukpyu deep sea port and the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project would represent major blows. Despite these and other factors likely preventing either side from backing down, the 28 November visit of Yohei Sasakawa, the Nippon Foundation chairman, to Nay Pyi Taw was notable in light of past efforts towards mediation in Rakhine State; Sasakawa was previously involved in ceasefires in the state in 2020 and 2022. Some observers were not hopeful; on 1 December, a former MP from Myebon Township told local media that Sasakawa’s discussion with SAC leaders would not result in any resolution to the current fighting.

However, even if fighting continues in the near term, room for negotiation may grow in the longer term as the AA faces mounting pressure to seek peace. The AA relies on the support of its Rakhine constituents, many of whom may grow weary as fighting drags on, food and other supplies dwindle, and movement and humanitarian support are stymied. If pressure from the Rakhine population grows strong enough, the AA may be forced to engage in negotiation, even if only aimed at a temporary pause, as seen in 2020 and 2022.

Trend Watch

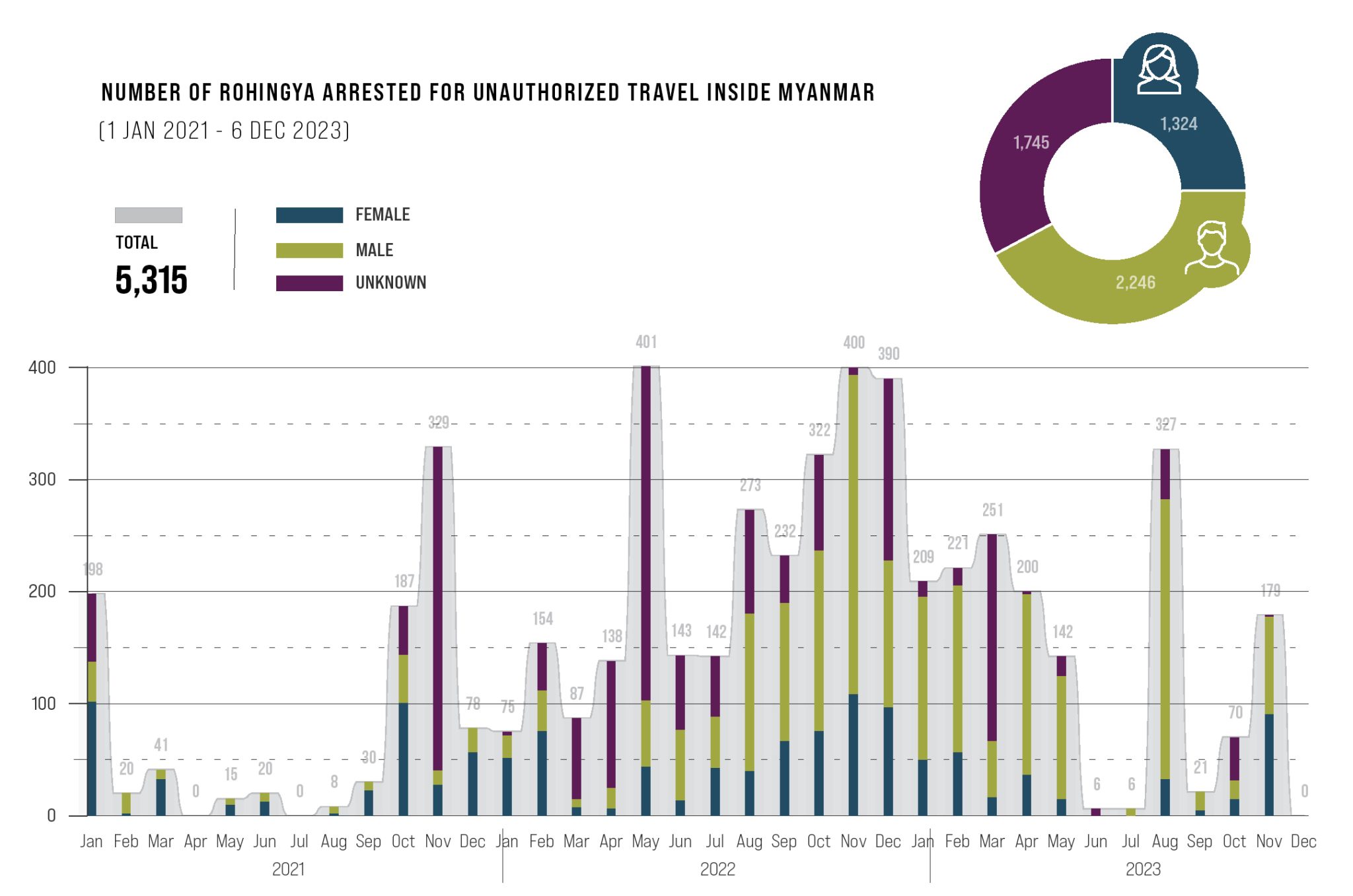

Number of Rohingya Arrested for Unauthorized Travel inside Myanmar (1 Jan 2021 – 5 Dec 2023)

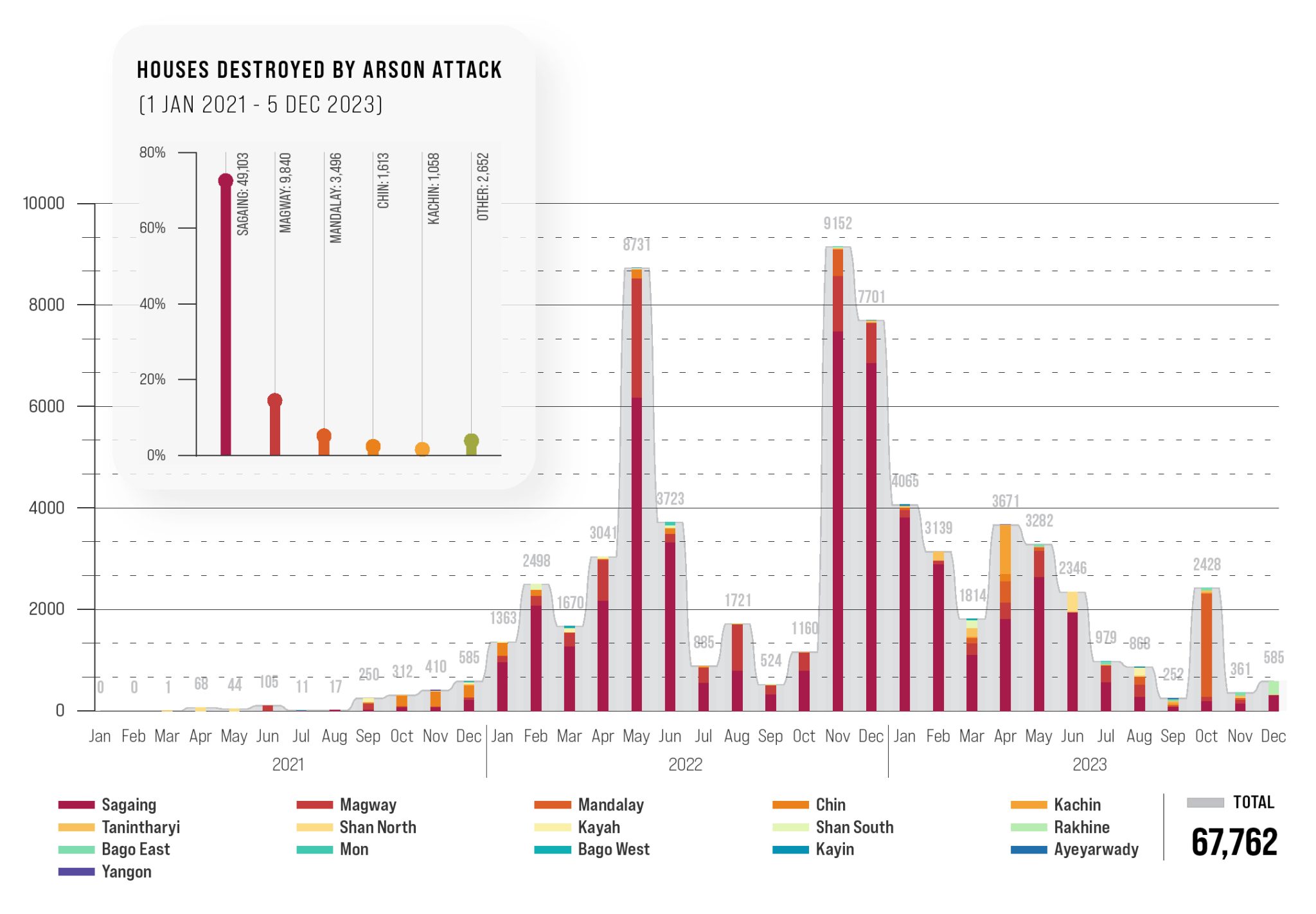

Houses Destroyed By Arson Attack (1 Jan 2021 – 6 Dec 2023)

Western Myanmar

Key Trends:

Armed fighting continued in Rakhine State, with much of it taking place around urban areas. The AA continued to attack and seize SAC positions, and the SAC continued to launch airstrikes and fire artillery from its bases and naval vessels. Safety and food security challenges persisted for civilians In many parts of the state. Meanwhile, Rohingya people remained particularly vulnerable, and some undertook dangerous journeys to leave the state.

Summary

Armed violence continued in Rakhine State, and severe transportation restrictions — including the closure of roads and waterways — has stymied humanitarian response and civilian efforts to seek safety. Nonetheless, a member of Arakan Responders for Emergency told local media on 29 November that fighting over the prior two weeks had displaced nearly 200,000 people in Rakhine State, including over 70,000 in Pauktaw Township. For the communities that can reach markets, the transportation restrictions have also triggered a dramatic increase in the cost of food and commodities, including fuel. A contributing factor to the high levels of displacement is the violence in urban areas, particularly after reports that the AA had captured Pauktaw town; the SAC has sent troops in Pauktaw, and frequent reports of civilian death, injury, displacement, and detention have followed.

While the SAC has significantly reinforced its naval presence in the state, it has consolidated its ground forces — moving police and other personnel to larger bases — and the AA has continued to overrun smaller SAC positions, including along the Myanmar Bangladesh border and the main highway leading to it. On 4 December, the AA reportedly captured one of two SAC hill positions near the Indian border, in Chin State’s Paletwa Township, where it had been fighting for 21 days. However, the AA has largely refrained from conducting attacks in urban areas, and it appears to remain sensitive — to a degree — to the impacts of fighting on Rakhine State civilians during the harvesting season.

Meanwhile, sources have told this analytical unit that Rohingya communities are under increasing pressure from both the SAC and the AA, and that Rohingya armed actors have also engaged in more frequent abuses against Rohingya communities. These pressures have likely contributed to the continued attempts of Rohingya people to leave the state under unsafe conditions that often result in detention or worse.

Primary Concerns

2. Rohingya People Trapped Amidst AA-SAC Fighting

Rakhine State

On 29 November, State Administration Council (SAC) troops in rural Buthidaung Township detained 10 Rohingya men from Kyar Nyo Pyin village for alleged ties to the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA). A Buthidaung Township resident told this analytical unit that elsewhere in the township, the ULA/AA told Rohingya people in Nyaung Chaung and Gu Dar Pyin villages to dig trenches for the AA to use while fighting against SAC forces, which the villagers did, and told them that it may later require them to leave the villages. Rohingya residents across Rakhine State have frequently reported stress and insecurity to this analytical unit as they feel caught between the SAC and AA, both of which demand that Rohingya not cooperate with the other.

Stuck in the middle

Since armed violence between the SAC and AA began again in Western Myanmar on 13 November, Rohingya populations not only have been vulnerable to the effects of armed violence, but they also have frequently found themselves under pressure from competing armed actors. This continues a pattern which has been emerging since 2018, when the AA began its offensives in western Myanmar; the SAC targeted Rohingya community members and leaders for arrest and detention on suspicion of AA or ARSA affiliation. As fighting rages between the AA and the SAC, Rohingya are caught in the middle, facing violence, abuse, and sometimes contradictory orders. The SAC’s instructions not to cooperate with the AA continue to instil fear in residents who have no real power to resist the demands of any armed actor. A resident in one Sittwe camp reported that SAC personnel called all Rohingya CMC members to a meeting in mid-November and told them not to collaborate with with ULA/AA, not to help Rakhine people evacuate from their areas, and to inform the SAC if any Rakhine people come to the Rohingya area for any reason.

Likewise, reports of an expanding Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) presence in northern Rakhine State over the last year have heightened community concerns, as the SAC has previously used ARSA presence as a pretence to attack Rohingya individuals and communities. On 28 November, a source in Maungdaw Township told this analytical unit that since fighting in Rakhine State began on 13 November, and SAC border police left their positions, there has been increased movement of Rohingya armed actors — the Arakan Rohingya Army (ARA) and ARSA, they said — in Rohingya villages in northern Maungdaw Township. The same source said that purported ARA members had recently detained, abused, and extorted Rohingya fishermen and businessmen, and that purported ARSA members had detained the administrators of several Rohingya villages. In the chaos of fighting, still more actors appear to have increased their activity, with disproportionate effects on Rohingya communities. As both the SAC and AA continue to compete for influence across the state, the impact on vulnerable communities—and particularly the Rohingya—needs to be monitored closely.

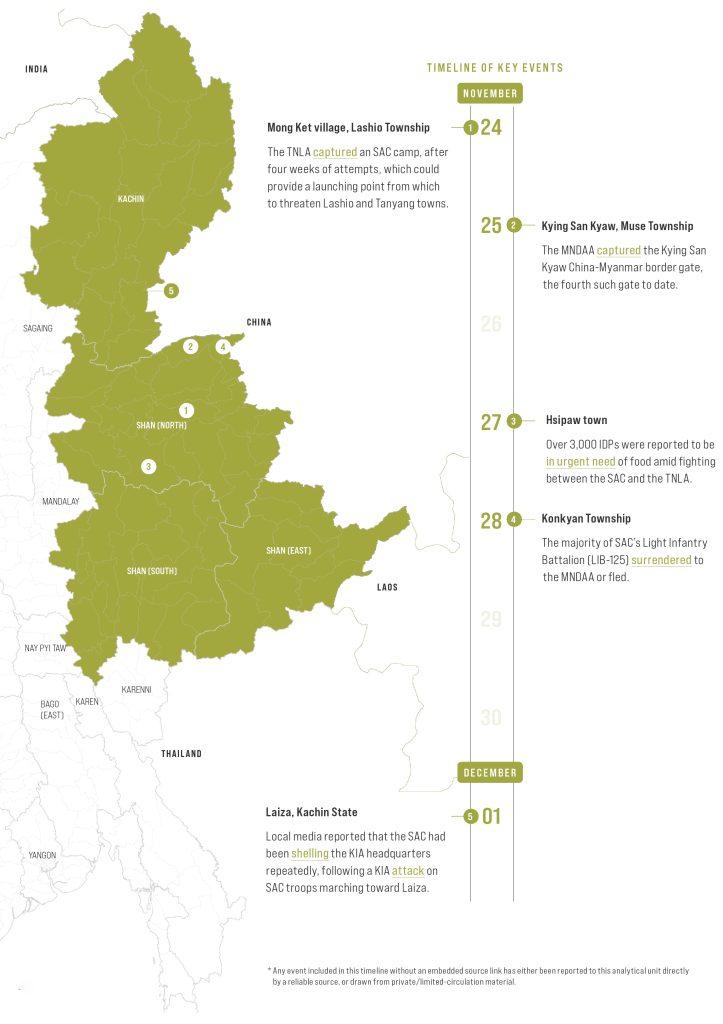

Northeast Myanmar

Key Trends:

Operation 1027, a large-scale offensive launched by resistance actors in Shan State late October, has sparked significant fighting between the SAC and EAOs in northeast Myanmar that appears poised to continue at a high intensity in the near term, and could inflame tensions between Shan State armed actors. In Kachin State, the trend of escalating armed violence over recent months continues with airstrikes around Laiza.

Summary

In Northern Shan State, fighting connected to Operation 1027 has continued to affect civilians, with tens of thousands displaced. The SAC has still not been able to recapture — or remove EAOs or PDFs from — key towns and transport routes, and at least five bridges have been damaged. Meanwhile, 3BA members claimed to have captured five Myanmar-China border towns, in one of which the MNDAA claimed to have established administrative mechanisms, and which host four border trade gates. As they continued to capture towns and other territory, reports emerged suggesting that the MNDAA has engaged in wide-scale recruitment, at least some of it by force. Imminent fighting in Laukkaing city could displace many thousands of people, and it could represent a humanitarian disaster in which response actors have little capacity to address needs; tens of thousands streamed out of the city after the MNDAA lifted a roadblock on 26 November, but many of those displaced have nowhere to go. Meanwhile, two Shan armed actors agreed to a peace deal, though the precise nature of the agreement and the motives behind it remain unclear.

Whereas Kachin State saw months of escalating armed violence prior to Operation 1027, the current nationwide resistance push seems to have shifted the focus of fighting to other areas — including neighbouring Northern Shan State and Sagaing Region. At the same time, a continued internet blackout across the state has meant that relatively few media reports have emerged over the past fortnight. Nonetheless, reporting suggests that fighting continues around Laiza — and likely elsewhere. In addition, some ethnic Lhaovo community leaders have reportedly begun recruiting youths from their ethnic minority group to serve in an SAC-aligned militia, raising concerns about recruitment practices and inter-communal tensions.

Primary Concerns

3. Displaced Laukkaing Residents Face Recruitment and Other Challenges

Laukkaing Township, Northern Shan State

On 29 November, local media reported that IDPs who were escaping Laukkaing city were forcibly recruited by the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) in Chinshwehaw town or between there and Laukkaing. Since 26 November, over 200 civilians have been recruited by the MNDAA in these areas, including individuals from the Pa Laung Self-Administered Zone (SAZ) (comprising Namhsan and Manton townships), others from Kutkai, Namhkan, Kyaukme, and Mogok townships, and members of ethnic minority communities from other townships. Such recruitment has tended to exclude ethnic Bamar (Myanmar), according to reports. Most of those who were forcibly recruited are allegedly Ta’ang individuals between the ages of 19-25. However, the reports caution that these figures represent only the instances reported to the media and the actual number of cases could be higher. Since mobile phones were also confiscated by the MNDAA, those detained reportedly lost contact with their families. A similar pattern of conduct was reported on 13 November: the MNDAA allegedly claimed it would help transport 26 monks to safety from Hay Moe Long monastery, Muse Township, but only released 22 from its custody and declined requests to release the other four (12-21 years old), whom it is said to have enlisted. Recent reporting suggests that the MNDAA is also recruiting local residents from outside of Special Region 1 (which, according to the MNDAA, includes Kokang, Kutkai, Hseni, and Monekoe Districts), in addition to individuals under 16 years old and monks. Many Kokang SAZ residents reportedly accept the obligation to serve at a certain age, but some criticised the forcible recruitment of monks into the military service. In response to criticisms of the group’s recruitment practices, an MNDAA spokesperson said, “Our policy mandates age of 16 and above for military service, regardless of the class, living in Special Region (1) [the Kokang SAZ]. We adhere to that principle.” Describing the experience of being assessed for potential service by the MNDAA but ultimately not selected, a Manton Township resident who had escaped Laukkaing said, “They primarily look at how we look. If we look Chinese or speak Chinese they take us. When they found people they wanted to recruit, they ordered us to leave our motorbikes and cars and then told us to get into their trucks and military vehicles. Some escaped after jumping off of the trucks but those who were on the military vehicles could not escape. They then rearranged us in Chinshwehaw and divided us to go separate ways. They told me to take the escape route.” Four other men from Lashio and 3 men from Kachin State (all ethnic Shan) were also forcibly recruited on 25 November. Describing their experience, a relative of one of those enlisted men stated, “When they were evacuating from Laukkaing to Chinshawhaw, the MNDAA detained them and burned their ID cards. They then told them to change into uniforms at the spot.”

These reports of forced recruitment have come amid wider concerns about Laukkaing residents being trapped in the city or facing major hurdles to returning home. An MNDAA roadblock on the route out of the city since the start of Operation 1027 reportedly left tens of thousands stranded there without water and electricity, with the road closure also driving scarcity of rice and other necessary provisions, leading to food shortages and increased prices. Reporting suggests that on 26 November, the MNDAA removed its roadblock, and thousands of IDPs evacuated the area on foot or using motorbikes, bicycles or cars. According to a woman who had been stranded in Laukkaing (but was speaking from Namtit town, in the Wa Self-Administered Division [SAD]), the MNDAA reopened the road on 26 November but many people remained in the city because they were afraid to venture out of it. Some who did leave appear to have faced robbery or extortion: on 28 November, members of a State Administration Council (SAC)-aligned militia in Hkar Shi village, Lashio Township, reportedly confiscated Chinese currency from people who had fled from Laukkaing. One of the victims described his experience:

“They told all motorists and car drivers to hand over all their Chinese Yuan. There were six of us and all of us had to pay one after another. They also asked us where we came from. When we said we came from Tangyan Town, they told us not to lie, and told us to take all our money out if we came from Laukkaing. When we told them we didn’t bring any, they even threatened us by pointing a gun at us saying, ‘if we find the cash on you, it’s gonna be bad.’”

Willing to serve?

The MNDAA’s statements and actions raise questions about its strength and concerns about internationally proscribed recruitment practices. As of 1 December, the Three Brotherhood Alliance (3BA) — of which the MNDAA is one of three members — had reportedly captured at least 230 SAC camps in Northern Shan State, as well as five China-Myanmar border towns (Chinshwehaw, Mone Koe, Kun Long, Pang Hseng, and Konkyan) and four border gates (at Chinshwehaw, Mone Koe, Pang Hseng, Kyinsankyawt). As well, on 30 November, the MNDAA announced that it had successfully established an administrative system in one captured border town, Muse Township’s Pang Hseng (Kyukoke). Despite these gains (or perhaps because of them), the MNDAA’s reported recruitment suggests that the group may need greater human resources to retain and administer newly-held territory — if not to continue fighting as part of Operation 1027. In addition to these isolated reports of forcible recruitment, the group has also called for large-scale recruitment, saying: “we don’t ask women to serve in the military. We use them in healthcare and office work. If there are two boys in the family, one must serve in the army. Since this is an emergency situation, we make no distinction between classes or ethnic groups. If they reach the age of 16, they are obliged to serve.” In any case, however, the MNDAA’s alleged recruitment practices over the past fortnight would appear to violate principles of international humanitarian law (IHL) and international human rights law, both of which proscribe the recruitment (and enlistment) of children under 15 years old. Under IHL, non-state armed entities are also likely prohibited from forcibly recruiting adults.

Laukkaing depopulated

As the prospect of fighting in Laukking city grows, so too does the impetus to flee, but roadblocks have made this difficult. On 1 December, the MNDAA stated that it had started the process of capturing Laukkaing, after issuing an 18 November statement warning Laukkaing residents living near SAC camps and institutions to evacuate and ordering Chinese citizens to return to China for safety, since it planned to capture Laukkaing. Even in the absence of large-scale fighting in the city, continued fighting and SAC heavy weapons fire in the Kokang SAZ have caused massive displacement, with Kokang natives fleeing to nearby camps and thousands of domestic migrant workers trying to return to their homes elsewhere in Myanmar. On 18 November, local media reported that over 30,000 residents of the SAZ were displaced and taking refuge at the makeshift BP-125 camp, established by the Kokang Parahita Group — a consortium with over 170 volunteers providing health care and other necessities for the IDPs. A Kokang resident reported that as their population grows, these IDPs are facing food, water, and electricity shortages. Despite daily water delivery from the Kokang Fire Department, and donations (bricks, three layer panels, bed frames) from local business owners, companies, and individuals donors, the camp officer reported that further support is needed, particularly since winter is coming. Due to the increasing number of IDPs, another camp—Yang Long Kang—was also reportedly established in Laukkaing. On 25 November, local media reported that SAC artillery struck the BP-125 camp, causing IDPs to flee to the BP-127 China-Myanmar border fence, where Chinese security forces pushed them back with tear gas.

On 26-28 November, the MNDAA claimed to have helped over 30,000 IDPs escape to Lashio and Nam Tit (Wa SAD) towns; there were already over 15,000 IDPs in Nam Tit as of 26 November. An IDP who arrived at Nam Tit camp reported that, while Wa authorities were providing for basic needs, the number of newcomers as well as pre-existing IDPs from Laukkaing, Kunlong, Par Hsin Kyaw, Chinshawhaw, Hopang has led to food, water and electricity shortages. In addition, because there were not enough aid vehicles to transport all IDPs to Lashio and Tangyan towns, some IDPs had to pay 400,000 Myanmar Kyat (~ 190 USD) to reach these places.

Travel out of Laukkaing has been impeded by numerous factors. Although there are four routes from Laukkaing to Lashio and onward, stretches of these roads have been disrupted, including by damage to the Kunlong, Kyinthi, Hseni Namtu, Pang Hpat, and Sin In bridges. Because the Hseni Bridge (connecting Hseni to Lashio) is destroyed, at least some people who fled Laukkaing took the forest route (route 4) from Nam Sa Lat village (Hseni Township) to Mong Yaw (Lashio Township), but their entry to Lashio town was blocked by an SAC toll gate near Nar Hpa village. Over 1,000 IDPs taking route 4 from Laukkaing, who arrived in Lashio Township on 28 November after three days of travel with no food, have been stranded in Nar Hpa village and taking refuge in the Nar Hpa and Tar Pong village monasteries. Furthermore, arrival in Lashio is no panacea. On 1 December, a local in Lashio told this analytical unit that almost all monasteries in Lashio are full of IDPs and that, while some NGOs were responding to their needs, support was not reaching Hseni, Hsipaw, or Kyaukme because of security, transportation, and access challenges. The responder said that his group was relying on local donations to support the IDPs, and that because prior donations to the group — around 80 Million Myanmar Kyat (~ 38,000 USD) — were running out and few new donations were coming in, he was concerned about support for an increasing number of IDPs, most of whom could not yet return home. The most direct route from Lashio to Mandalay (the national highway) has been rendered impassible by damage to the Sin In and Kyinthi bridges, leaving IDPs no choice but to take an indirect and more expensive route back home; those who cannot afford it will likely remain stranded in or around Lashio.

4. Lhaovo Leaders Recruit for Militia

Myitkyina and Waingmaw Townships, Kachin State

On 23 November, Kachin news media reported that 10 ethnic Lhaovo leaders in Myitkyina and Waingmaw Townships were preparing to establish a militia, in cooperation with the State Administration Council (SAC), to represent the Lhaovo people and were recruiting new members in the same two townships. Their actions reportedly followed a request, from the SAC, for them to form a militia force and collaborate with the Lisu militia, which is already working in cooperation with SAC in Waingmaw Township. According to the same report, the alleged forced recruitment of young people to form the militia has sparked criticism among Lhaovo people in Kachin State, divided Lhaovo community members, and resulted in a migration of young people to urban areas or elsewhere to avoid having to serve. Following objections from the public and a call from the Central Committee of Lhaovo Literature and Culture for “Lhaovo” not to be used in the names of groups not representative of the Lhaovo people, the militia is reportedly preparing to rename itself the “Tsawlaw Militia Force.” A resident of Wuyang village, in Waingmaw Township, told this analytical unit that approximately 10 young Lhaovo men from there and two other villages in Waingmaw Township were forcibly recruited in October 2023, and that a first batch of approximately 50 people from Waingmaw and Myitkyina townships were undergoing military training, along with new Lisu militia recruits, at the SAC’s LIB-321 in Nyaungpin village, Waingmaw Township. A Waingmaw town resident told this analytical unit that those supporting the SAC and advocating for the formation of a Lhaovo militia, against the will of the Lhaovo people, are only pursuing selfish interests and do not represent the entire Lhaovo tribe.

Minority reports

The formation of a Lhaovo militia (or Tsawlaw Militia) could exacerbate interethnic tensions and territorial disputes in Kachin State, and even worsen outcomes for Lhaovo people. Reporting suggests that there are at least 30 militias — including groups claiming to represent Lisu, Rawang, and Shanni ethnic minorities — working with the SAC in Kachin State, which the SAC equips but allows the freedom to define their areas of operation, distribute power, and manage natural resources. Such arrangements likely benefit the SAC by increasing the number and spread of fighters on which it can call when fighting the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), and by increasing opposition to the KIA among ethnic minorities within the state. After the coup in 2021, Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO) Chairman Nban La said that the SAC was forcing civilians to form militia groups in Kachin State to gain support in military politics, and the KIO declared all People’s Militia Forces and Border Guard Forces formed by SAC to be its enemies. Relations with the SAC also seem to confer power and lucrative business opportunities unto militia leaders. In the best of cases, these militias may provide a degree of protection for ethnic minorities subjected to abuses by ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) associated with other ethnic groups. However, they also have the potential to worsen relations between ethnic groups and — as reporting suggests in the case of the Lhaovo militia — stoke intra-communal disagreement. As well, such militias have themselves been the perpetrators of abuses against civilians in Kachin State — beyond forced recruitment, which can remove work and education opportunities and incur distress, if not injury or death — including extortion, abduction, and killing.

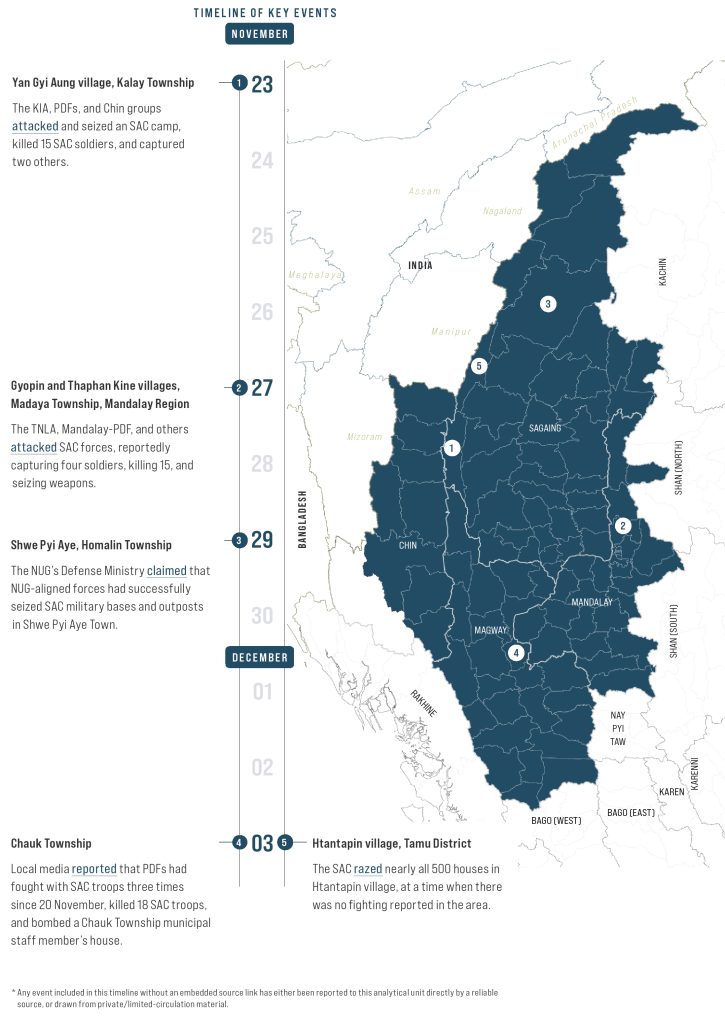

Northwest Myanmar

Key Trends:

Fighting in the northwest continues at a high level, as it had even before Operation 1027 cascaded into a nationwide escalation in armed violence. Resistance actors continued to capture towns in Chin State, and other groups attacked SAC positions around towns in Sagaing Region. Meanwhile, the SAC continued to torch houses, kill and abuse civilians, and launch airstrikes and artillery in response to resistance attacks.

Summary

Chin resistance forces continued to gain ground, seizing control of two towns in Matupi Township, where the CNF said it would administrate in cooperation with local groups. Chin forces also launched operations in Hakha and Thantlang towns, ostensibly aimed at capturing them.

In Sagaing Region, SAC raids and intense levels of violence — including the razing of hundreds of homes — continued to drive displacement. At the same time, resistance groups have retained control of Kamphet and Kawlin towns, and claimed to have set up an administration in the latter. On 30 November, the NUG announced that it had seized over 44 billion Myanmar Kyat (~ 20.9 million USD) from five private bank branches in the Kawlin Town. NUG-affiliated groups launched attacks in other urban areas of the region, and claimed to have overrun SAC positions around Shwe Pyi Aye, Tigyaing, and Taze towns. In response to the attacks in Tigyaing town, SAC troops burned down nearly two-thirds of the town, and SAC airstrikes and shelling killed more than 100 people, locals said. Because it could potentially link resistance actors from Northern Shan State to western Myanmar, Sagaing Region has assumed growing importance amid the nationwide escalation of resistance activity since late October. By using pathways through Sagaing, resistance actors could potentially direct a flow of arms to Chin groups, as well as direct ordnance and supplies to PDFs in Magway Region and the AA in Rakhine State. Local experts contend that a secured route through Pinlebu and Ye-U townships could facilitate these resistance measures and disrupt SAC efforts to reinforce its troops and supplies in ethnic border states.

In Magway Region, SAC forces continued to abuse civilians, and resistance groups continued to target SAC positions and individuals affiliated with the SAC. Two resistance groups fired rockets at an SAC weapons factory, at least the second such attack in the region this year. Fighting also continued in Mandalay Region, nominally under the banner of “Operation Shwe Pyi Soe”, which involves PDFs as well as the TNLA.

Primary Concerns

5. Chin Groups Continue to Capture Towns

Matupi Township, Chin State

On 24 November, joint forces of Chin National Army (CNA) and Chinland Defense Forces (CDFs) took full control of Lailenpi town in Matupi township after seizing a State Administration Council (SAC) base and police station in the town, following fighting there since 18 November. The Chin joint forces killed three SAC soldiers, including a deputy battalion commander, during the fighting. No casualties were reported from the Chin groups’ side. According to local media in India’s Mizoram State, on 28 November 30 SAC soldiers — who had fled the fighting with full arms on 24 November — reportedly arrived at an Assam Rifles camp in Tuipang village, in Mizoram State, and were later repatriated by the Indian Air Force via the Moreh-Tamu border on 29 November. Local media claimed that Assam Rifles troops had entered Para, a village in Matupi Township, to evacuate the fleeing SAC soldiers into India. On 29 November, the same Chin joint forces seized Rezua town, also in Matupi Township, after four days of heavy fighting and their eventual capture of an SAC base and police station. Forty SAC troops at the Rezua base are said to have surrendered — along with their families — to the Chin groups, which confiscated all weapons and equipment from the base. One CNA fighter and three CDF fighters were killed during the fighting; there were no reported SAC casualties. SAC airstrikes killed four civilians and injured three, and destroyed nearly 50 resident houses, a Christian Church, and school in Lailenpi town, while no civilian casualties were reported in Rezua. The entire population of both towns (around 7,000 people) fled to nearby villages or to Mizoram during the fighting, but the vast majority have returned since the Chin groups took control of the town.

There has been heavy fighting in Chin State since 13 November, when the same Chin groups launched offensive operations against SAC forces in Rihkhawdar town, which they eventually captured. The operation and capture followed the start of Operation 1027 in Northern Shan State; on 30 October, the Chin National Front/Army (CNF/A) issued a statement welcoming Operation 1027 and urging Chin groups to use it as an opportunity to launch operations against the SAC. In total, during 13-24 November, Chin groups seized three towns and six SAC bases, and gained two others that SAC forces abandoned.

New sheriffs in town

The resistance’s seizure of towns in Chin State presents new administration and coordination challenges for groups that remain fractured despite efforts by some to form a state-wide governance structure. Overall, seven towns have fallen to Chin groups since February 2021, while the SAC retains some degree of control in nine major towns with township administrations, as well as two smaller towns. Meanwhile, CDF-Hakha, one of the largest new resistance groups in the state, announced on 27 November that it had launched the Rung Operation, targeting SAC forces in the state capital, which it said was meant to support Operation 1027; on the same day, CNA and CDF members fought against the SAC in Thantlang, reportedly aiming to capture the town; and on 27 November, Chin groups said they would continue to increase urban operations, suggesting that fighting in the state is not likely to end soon. Each town the resistance has seized in Chin State falls within the operational area of one or more Chin groups, meaning that administration of towns — including the administration of humanitarian services — would likely need to involve coordination between groups that are not fully aligned with one another. On 22 November, the CNF announced that, in the towns and areas where it has taken over, it will administrate jointly with the local resistance groups active in those locations (e.g. with CDF-Hualngoram in Rihkhawdar, with CDF-Mara in Lailenpi, and with CDF-Zotung in Rezua). However, it remains unclear how this will be received by each of the other groups and, even if they are amenable, how it would play out; while cooperation is likely to all groups’ benefit, there could just as easily be competition over resources that makes such cooperation difficult. At the same time, efforts toward statewide governance hold promise, even if several similar past efforts in the state have been unable to achieve this. Sources told this analytical unit that the Chinland Council Conference — which aims to adopt the interim Chinland Constitution in order to form the Chinland government — began on 3 December and would last several days. Even if various Chin groups have only partial control of the state, a constitution and government — if achieved — could provide a much-needed building block for the development of governance in newly-captured territory.

6. Resistance Fires Rockets at SAC Weapons Factory

Sidoktaya Township, Magway Region

On 30 November, the People’s Revolution Alliance-Magway (PRA-Magway) and Z Fighter Guerilla Group fired more than 20 rockets at the State Administration Council’s (SAC) No. 20 Defense equipment factory in Sidoktaya Township. Reports suggest that there are around 400 SAC personnel at the factory, which mainly manufactures weapons that fire 25mm and 30mm munitions. The PRA-Magway leader said that the weapons used in the attack had been hand-made, and that the group would carry out operations and attacks in future but would need more money to do so. He also said the group was investigating the destruction and possible SAC casualties; Z Fighter Guerilla Group said that firefighters were extinguishing the factory building and gunpowder storage. Locals reported hearing a loud explosion in the factory and stated that the fire on its premises burned throughout the whole night, so they considered it likely that the SAC incurred considerable losses. The SAC did not make any public disclosure related to this incident, but did patrol around the factory and conduct searches in the surrounding jungle after the attack. The following night, on 1 December, the SAC fired at least 20 shells around the factory and Sidoktaya town. Locals said that troops stationed at the factory had abused nearby villagers prior to this incident, including by entering villages along the Ngape-Sidoktaya road, demanding money from residents, seizing residents’ phones, threatening community members, and distributing misinformation.

Rocket power

As under-resourced resistance groups in Magway continue to attack SAC factories and other positions, civilians living nearby are likely to bear the brunt of often-violent SAC responses. Regarding the 30 November attack, the PRA-Magway leader said that this would result in a huge loss for the SAC because weapons from the factory are used in Chin and Rakhine States and elsewhere in Myanmar. He also said that there are many SAC equipment factories in the PRA-Magway’s operational area, which includes Ngape, Minhla, and Sidoktaya Townships. Taken together, these statements suggest that the PRA-Magway — and potentially other groups in Magway Region — may continue to conduct attacks on SAC factories and positions. There are 25 defence equipment factories in Myanmar, 15 of which are in Magway Region (and the others in Bago and Yangon Regions and Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory), one of which resistance groups attacked in April this year. However, the SAC often responds to such attacks with violence against civilians residing in areas near the site of the attack, including through the use of airstrikes in what Amnesty International has averred to be collective punishment. While the consequences of the 30 November attack remain unclear, resistance groups will have to continue to anticipate and navigate the potential blowback for civilians of such operations.

7. Resistance Captures SAC and SNA Camp, UNLF Camp

Tamu Township, Sagaing Region

On 22 November, the combined Tamu People’s Defence Force (PDF), Chin National Defence Force (CNDF), Rawn Chinland Defence Force (RCDF), and Kuki National Army-Burma (KNA(B)) — originally part of the KNA, which operates in India — attacked and captured a State Administration Council (SAC) prison camp in Thanan village, Tamu Township, and detained the camp commander. On the SAC side, the fighting also involved the Shanni National Army (SNA) and two ethnic Meitei groups based in India’s Manipur State, the People’s Liberation Army-Manipur (PLA-MP) and the United National Liberation Front (UNLF) — both members of the Manipur Peoples Liberation Front, an umbrella organisation of separatist groups in Manipur, and possibly acting as one in Myanmar. Continuing on 23 November, the combined PDF attacked and captured the UNLF/PLA-MP camp, between Thanan village and Homalin Township’s Tonhe village. They detained 11 SNA and one Meitei soldier in the fighting, and seized weapons and ammunition, several trucks, and SNA arm badges. On 24 November, three SAC helicopters shot at and bombarded the roughly 200-household Thanan village three times, destroying six houses and causing residents of Thanan and nearby villages to flee to rice fields, the jungle, and Manipur; locals said that 3,000 people fled from seven villages in Tamu Township, and a Manipur-based news source reported that around 600 Myanmar individuals entered Manipur. The leader of the Tamu PDF said that people fled to Manipur because there are no IDP camps in Tamu. By contrast, a Thanan village resident told local media that she and others fled to the jungle instead because they feared arrest by Manipur police.

Tamu melee

The sheer diversity of actors involved in these incidents in Tamu Township demonstrates the complicated inter-communal dynamics in the area. The KNA(B), a Kuki armed actor fighting against the Myanmar military, is an offshoot of the KNA, which operates in Manipur, where there is ongoing violence between ethnic Kuki and ethnic Meitei people. The UNLF and PLA-MP are Meitei armed actors based in Manipur but allegedly cooperating with the SAC, likely as part of a safe harbour agreement, following India banning the groups. While there are far fewer Meitei people in Myanmar (where they are called “Kathe”) than in Manipur, and this analytical unit has seen no evidence of Kathe people supporting the two groups, Myanmar is a highly diverse (and often fragmented) place in which people often rally around ethnic or other cultural markers. Thus, the dynamics between all of these groups could impact relations between different communities, particularly if there are perceptions among the communities of abuses against them by the armed actor associated with the other side. Such perceptions may already exist: according to the KNA(B), the UNLF/PLA-MP has helped the SAC since the beginning of the coup, including by cracking down on civilian protesters; and in 2021, an unnamed Indian intelligence chief told local media that the SAC was using the UNLF and PLA-MP to drive back and block Myanmar refugees from entering Manipur. Meanwhile, the SNA embodies just this issue. While reports of SNA operation in Tamu Township are infrequent, at least one other instance was reported this year, and the SAC may be leveraging the SNA for military benefit in Sagaing Region. The SNA claims it is trying to establish a Shanni State that would comprise at least parts of Sagaing Region and Kachin State. The Myanmar military has historically capitalised on existing intercommunal tensions by arming and encouraging the formation of militias by smaller ethnic groups like the Shanni, members of which are said to hold historical grievances against the Kachin and Bamar groups related to political marginalisation and lost territory of Shanni people. Amid continued tensions in Tamu Township, there could be similar trends among other communities.

8. SAC and Pyu Saw Htee Kill 18 Civilians

Monywa Township, Sagaing Region

On 2 December, State Administration Council (SAC) troops and Pyu Saw Htee members based in Taw Pu village raided the roughly 400-household Kya Paing village, in Monywa Township, where they razed almost all of the houses and reportedly killed at least 11 people before leaving the same evening. Many people fled from Kya Paing and nearby villages, but some people and local People’s Defence Forces (PDFs) returned and searched for dead bodies; on 3 December, locals said that they found 18 dead bodies in the village, allegedly killed by SAC forces during their raid; it is unclear where this discrepancy comes from. The raid came a day after the Monywa District PDF and allies attacked Pyu Saw Htee members in Taw Pu village — reportedly a Pyu Saw Htee stronghold near Monywa — and reportedly seized the Pyu Saw Htee camp there. A family member of one of those killed told this analytical unit that SAC forces had arrived at the village without warning, leaving no time for people to escape; they said that approximately 60 people were abducted and 11 men killed. One villager said that some people dared not return to Kya Paing village due to concerns that the SAC had planted landmines there.

Fire in the home

Protection continues to be a critical concern in Sagaing Region, where the SAC has carried out diverse and extensive abuses against civilians and where communications channels are often lacking. According to local research group Nyan Lin Thit Analytica, during February 2021-August 2023, SAC forces committed at least 175 massacres (killing more than five people at once) in seven states and regions, killing 1,794 people. Killings and other abuses since the coup have been particularly rife in Sagaing Region, where SAC forces reportedly burned down 58,397 houses (as of 31 October 2023) and 816,500 people were displaced (as of 10 November 2023). Although local PDFs and volunteers have early warning practices, most of those practices remain ineffective due to technical limitations, under frequent phone and internet blocks. Locals have told this analytical unit that in some townships of Sagaing and Magway Regions, alternative internet sources (e.g. Starlink) have reportedly allowed local people to be more resilient to SAC raids and airstrikes. However, the use of such services is not widespread, and there are often insufficient early warnings to help prevent incidents such as that on 2 December. The importance of early warnings systems has only grown since the start of Operation 1027 in Northern Shan State: the National Unity Government (NUG) declared that it would collaborate with others in the operation; and PDFs nominally under the NUG chain of command, in addition to other groups, have launched more ambitious attacks against SAC positions and been met with predictably severe SAC actions. On 3 November, the joint forces of KIA, AA and NUG’s PDFs attacked four SAC outposts in Kawlin town, Kawlin Township, in response to which the SAC conducted at least four airstrikes and shut down electricity and communications networks in the town. On 30 November, the SAC launched airstrikes on school and clinic buildings in Ywar Shay and Taung Kyaung villages, and another airstrike killed a man in Taze town (all in Taze Township) following PDF attacks on its outposts in Taze town. Continued SAC bombing in Tigyaing town, since the KIA and PDFs launched an attack there, has reportedly destroyed two thirds of the town and killing more than 100 people. As such attacks proceed, it is critical that communities be equipped with early warning systems capable of helping them avoid fighting and other dangers.

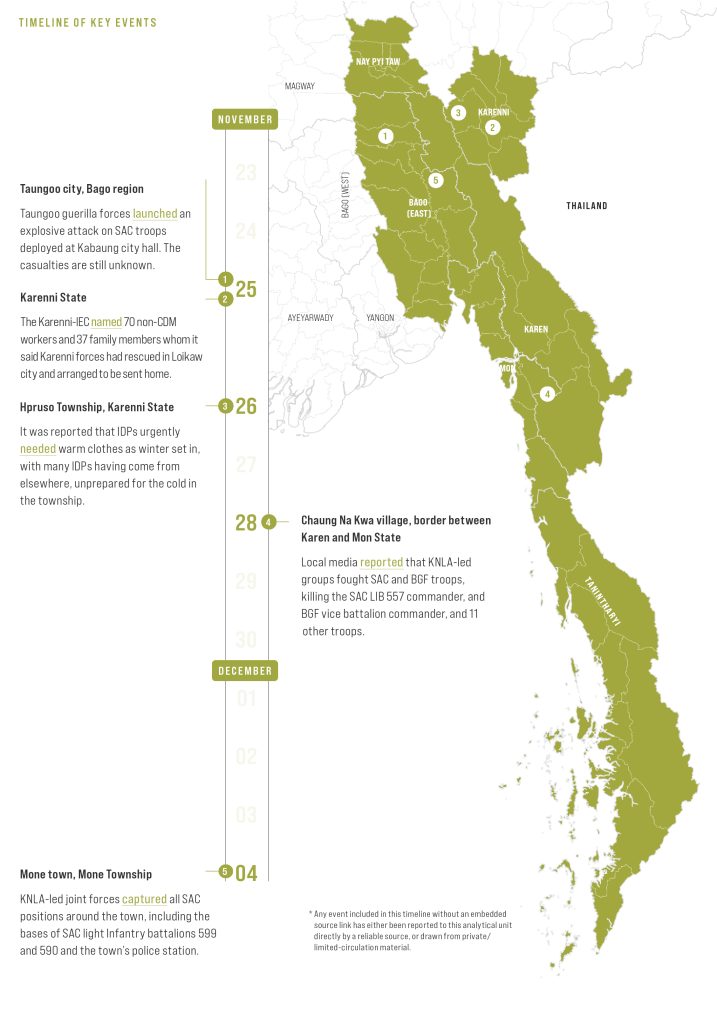

Southeast Myanmar

Key Trends:

Karenni resistance forces continued their attacks in the state capital of Loikaw in Operation 1111, apparently capitalising on the momentum of Operation 1027 and nationwide escalation, but humanitarian needs continued to rise. In Karen State and Eastern Bago Region, KNLA-led fighters attacked SAC positions around towns — including in Kawkareik town and all SAC positions in Mone town — in an apparent shift from previous tactics.

Summary

Intense fighting in the Karenni State capital of Loikaw has seen continued territorial gains for Karenni resistance actors, as well as continued displacement and elevation of humanitarian needs for civilians. Many Loikaw residents have fled, as have international response actors, leaving local responders struggling to address higher needs. Also in Loikaw city, more SAC troops reportedly surrendered to resistance forces, and the Karenni IEC tried to address the treatment of detained troops and non-CDM workers. The SAC pummelled the city with artillery fire and airstrikes.

Urban attacks continued to increase in Karen State and neighbouring Bago Region. KNLA-led fighters launched at least one attack in Taungoo city, Bago Region, and on 4 December others reportedly overran all SAC positions in the region’s Mone town. Starting on 1 December, KNLA-led fighters began a bold offensive in Kawkareik town, along the Asia Highway in Karen State. Town residents reported that many SAC personnel had fled beforehand and that the SAC administration there was no longer operational. The fighting blocked traffic and movement on the Asia Highway, disrupting commerce and the impeding people from fleeing Kawkareik town.

Primary Concerns

9. KNLA Attacks Kawkareik Town

Kawkareik Township, Karen State

On 1 December, Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA)-led forces attacked State Administration Council (SAC) positions in and around Kawkareik town and captured SAC’s the Kawtnwe camp, near the town, where SAC troops allegedly raised a white flag and surrendered — though the number of surrendering soldiers has not been publicly reported. Just on 1 December, SAC airstrikes and artillery killed at least five civilians. Intense fighting, which continued until at least as recently as 4 December, followed a 17 November Karen National Union (KNU) statement requesting SAC personnel to leave their posts by the end of that month; Kawkareik town residents said on 1 December that many SAC personnel had fled since the KNU warning, as had most residents, and that the SAC’s administration in the town was no longer functioning. Local media reported on 30 November that the SAC, seeming to heed the statement, had closed down the road connecting Kawkareik to Na Bu, further south in Kawkareik Township. Once fighting began, travel through Kawkareik on the Asia Highway became impossible. On 2 December, transport became even more difficult as SAC and Border Guard Force (BGF) troops tried to close ways into and out of the town, and fired at civilians trying to escape the town, leaving some people trapped. On 1 December, local media reported that fighting had left both civilians and commercial trucks stranded on the road. On 4 December, local media reported that 11,700 people had been displaced from 24 villages due to this fighting — a number not including five other villages and Kawkareik town because of barriers to communication. Another media source reported that humanitarian workers from elsewhere in the state were helping elderly people, children, pregnant women, and their families move to safer places.

Out of the town

Recent KNLA attacks on SAC positions around urban areas — and particularly those in Kawkareik — mark a shift that could lead to more significant losses for the SAC and greater displacement for civilians. In addition to Kawkareik, KNLA-led actors launched attacks on Mone town, in Bago Region, where they reportedly captured all SAC positions; some media sources reported that resistance actors had taken control of the town. The timing of these urban attacks suggest some connection with Operation 1027 in Northern Shan State; while there is little known evidence that the KNU is aligned with the Three Brotherhood Alliance, Operation 1027 has resulted in widespread perceptions that the SAC is weaker than previously assumed, which resistance actors in the southeast (and elsewhere in Myanmar) may have interpreted as an opportunity to expand their own territory or otherwise advance their interests.

Kawkareik holds particular significance for both the SAC and the resistance, as it sits along the Asia Highway. The road, which connects the economically important Thai border crossing at Myawaddy with Yangon and points farther into Myanmar, runs through Karen State and has long been tightly held by the Myanmar military. Myawaddy is the largest trade point along the Thai-Myanmar border, with a reported USD 1.74 billion in trade from April 2022 to January 2023, and interruptions to the SAC’s access to Myawaddy would likely affect a significant portion of this trade. A severance of the route at Kawkareik — even if temporary — would also hurt the SAC’s ability to send troops and supplies to its camps along the border and elsewhere in Karen State. By a similar token, roadblocks around Kawkareik stand to disrupt economic activity that benefits civilians, disrupt humanitarian response, and make it harder for civilians to find safety.

10. Operation 1111 Continues in Loikaw

Loikaw Township, Karenni State

On 30 November, a Karenni Nationalities Defence Force (KNDF) official said that, on the 20th day of Operation 1111, fighting and State Administration Council (SAC) airstrikes continued but resistance groups could move freely and deploy their members to at least half of Loikaw city. Intense fighting in the Karenni State capital since 11 November reportedly dislodged the SAC from multiple positions, left 200 SAC troops dead, and resulted in the surrender of over 60 SAC troops. It has also turned the city into a warscape; local media reported that, during those same 20 days, the SAC conducted 357 airstrikes there. A colonel in the Karenni Army told local media that, just on 29 November, the SAC conducted an estimated 60 airstrikes using 500-pound bombs and fired numerous artillery shells, destroying many homes. On 1 December, the Loikaw People’s Defence Force (PDF) and another group, Falcon Wings, launched a drone attack on SAC positions in Loikaw that left an SAC ammunition building in flames.

The fighting — and particularly SAC airstrikes and artillery fire — has displaced tens of thousands of civilians and placed further strain on communities throughout the area. On 28 November, local media reported that SAC troops forced around 60 monks, sisters, and elderly and sick people sheltering in a catholic church to leave the church, and then set up camp there. On 29 November, local media reported that civilians injured by SAC artillery attacks would not be able to receive treatment because there is poor transportation and people are afraid of being interrogated by SAC troops while transporting patients. A resident in Loikaw city expressed “the terror of hearing the deafening sounds of the explosions. Every day, we worry about our safety.” He added that there is also no connectivity in the town, so they can’t receive news or call anyone for help.

On 2 December, U Banyar, second secretary of Karenni State Interim Executive Council (IEC), emphasised the direness of the situation and urgently called for cross-border aid from United Nations (UNs) agencies with the support of the Thai government. He emphasised that SAC roadblocks hindered volunteer groups’ ability to purchase and deliver necessities to IDPs, led to shortages in the state, and significantly increased food costs. Volunteer groups likewise stressed the importance of cross-border aid in cooperation with local organisations, saying this would be more effective than aid through INGOs based in SAC-controlled areas.

Low in Loikaw

The focus of Operation 1111 on gaining control in Loikaw remains a bold strategy with potentially dire humanitarian consequences. The ultimate designs of the operation remain unclear, with some locals telling this analytical unit that it is intended to capture Loikaw city, and a CDNF deputy commander claiming that the rationale is to “tear” the SAC’s central command — responsible for the entire Karenni State — and destroy the SAC’s administration within the city. In any case, at the launch of Operation 1111, the apparent attempt to remove the Myanmar military from a state capital was unprecedented. It has also contributed to widespread suffering in Loikaw. On 2 December, local response groups estimated that the fighting since November had displaced 45,000 people in Loikaw city. IDPs will likely face challenges accessing basic necessities such as food, shelter, and healthcare. Rising prices of essential goods will also limit the accessibility of basic goods where available, and travel restrictions have thus far prevented local responders from reaching IDP populations. Despite many people fleeing the city, others remain trapped there by fighting and repeated SAC airstrikes and shelling. The evacuation of international humanitarian response staff from the state is also likely to make response more challenging — and, even more so, it is a testament to dangers facing civilians who remain. As resistance groups continue trying to capture the city, the crisis is not likely to end soon, and humanitarian access to the area is extremely challenging as responders must navigate control and permissions by both SAC and resistance forces.

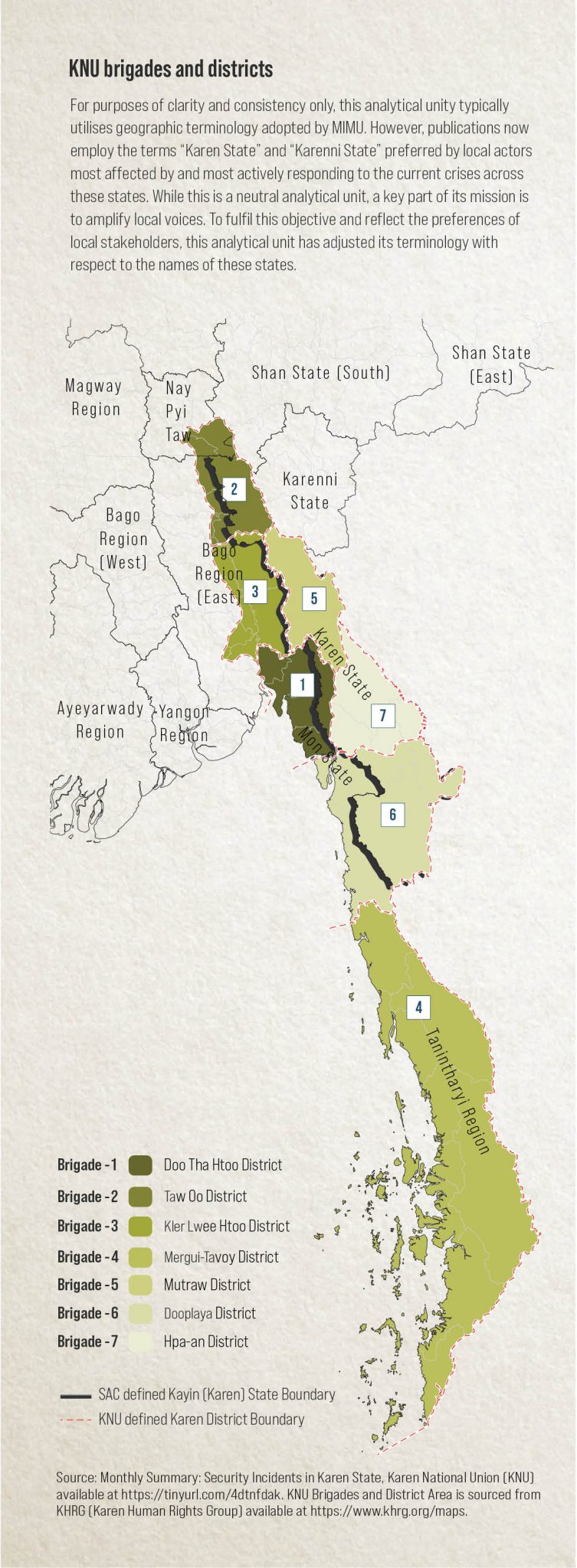

For purposes of clarity and consistency only, CASS typically utilises geographic terminology adopted by MIMU. However, CASS publications now employ the terms “Karen State” and “Karenni State” preferred by local actors most affected by and most actively responding to the current crises across these states. While CASS is a neutral analytical unit, a key part of its mission is to amplify local voices. To fulfil this objective and reflect the preferences of local stakeholders, CASS has adjusted its terminology with respect to the names of these states.